By CAPT Mark Poster, CMI

The occurrence of vessel collisions raises several pertinent questions: despite the existence of the Navigation Rules, why and how do vessel collisions still happen? Don’t the Navigation Rules exist to direct what proper actions vessels are to take as they approach a “risk of collision” situation? And then, the next key consideration is: when exactly during the approach evolution is a “risk of collision” created? Once the encounter becomes such a risk, what additional Rules apply and when do they become activated and compulsive? These are the questions that law enforcement, accident investigators and courts seek to answer; to ascertain the circumstances during the pre-collision stage and help determine which vessels are responsible for taking or failing to take specific action at designated times.

The Navigation Rules and Regulation Handbook dated April 2025 includes both sets of rules; International and Inland. Officially known as “International Navigational Rules”, aka the “72 COLREGS” (short for “Collision Regulations”, and the “Inland Navigational Act of 1980” or just “Inland Rules”. The Inland Rules will apply and be referenced in our Funnel. Each specific Rule will be abbreviated, such as Rule 1 is R1.

All operators are required to follow, if not to know, these Rules. As we navigate through each stage of our Funnel, each Rule is identified as it applies. Our example below will be for vessels “in sight of one another” (R11), not in a “narrow channel” (R9), nor “in or near an area of restricted visibility” (R19). The conditions during our example situation will be on a good day in calm, open waters without restrictions. The two recreational power vessels are of a similar size, type, and maneuvering capabilities.

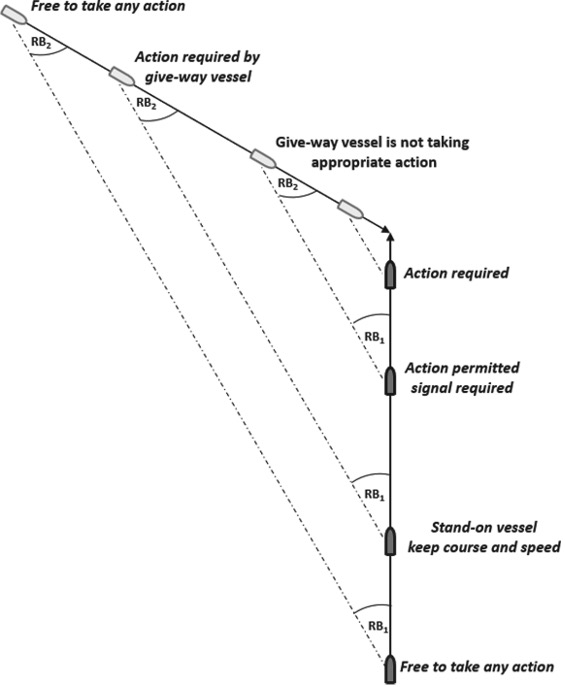

The Collision Avoidance Funnel shows how maneuvering options decrease and collision risk increases as time and distance are squandered, often leading to collisions. This idea is illustrated in several similar versions, and some ideas and quotes below are from concepts from Farwell’s Rules of the Nautical Road, Ninth Edition. This is my interpretation of a scenario highlighting the possible timing and application of the Rules during an encounter between vessels.

The Funnel concept breaks the approach into several stages as each vessel draws closer as they enter their own Funnel, descending further into an ever-tightening predicament. Think of two funnels with the small ends touching, each funnel representing the angle of approach of the two vessels.

These imaginary funnels, however, are open at the far narrow end, providing an escape. Once the two funnels touch, they become cones, and the touching tips have become the Point of Impact. Whenever a collision is narrowly avoided, it remains an open Funnel.

Each of the stages represents the changing relationship between the vessels. This, in turn, determines the relevant NAVRULES application and requirements for each vessel. As the approach distance closes, less time is available to decide and maneuver. The risk of collision develops until vessels are first in a close-quarters situation, and then in immediate danger of collision. A collision will occur if the vessels stay on this course or take improper action. The idea can also be thought of as the “Funnel of diminishing options”.

Assess the pre-collision events to determine the situation, roles, and actions required.

The Collision Avoidance Funnel describes five stages as the situation progresses. Each stage activates specific Rules that must be obeyed.

To better understand, think of the Rules in a chronological, logical order as we begin the voyage and encounter another vessel.

- Stage 1: Long Range / Free Movement

- Stage 2: Risk of Collision / Risk Escalation

- Stage 3: Close-quarters situation / Narrowing options

- Stage 4: Immediate danger / In Extremis

- Stage 5: Collision

All stages of the Funnel are subject to an initial group of Rules that employ strong, unambiguous, all-inclusive language to ensure complete understanding of their intentions. These Rules are constant, ongoing, perpetual, and never-ending, demanding high vigilance, attention, and situational awareness whenever a vessel is underway.

A quick review/reference to these initial Rules, and language, is provided below (highlights added):

33 U.S.C. Part 83, Part A – General

- Rule 1 – Application “These Rules apply to all vessels…”

- Rule 2 – Responsibility “Nothing in these Rules shall exonerate any vessel…”

- Rule 3 – General Definitions

Part B – Steering and Sailing Rules Subpart 1 – Conduct of Vessels in Any Condition of Visibility

- Rule 4 – Application: “Rules in this subpart apply in any condition of visibility”

- Rule 5 – Look-out “Every vessel shall at all times…”

- Rule 6 – Safe Speed “Every vessel shall at all times …”

- Rule 7 – Risk of Collision “Every vessel shall use all available means”

- Rule 8 – Action to Avoid Collision “Any action taken to avoid collision shall be…”

Illustration of “Constant Bearing / Decreasing Range” situation in Rule 7(d) Risk of Collision “…shall be deemed to

exist if the compass bearing of an approaching vessel does not appreciably change, …”

Stage 1: When the distance between two vessels is such that maneuvers by one would have no immediate effect on the other, there is no risk of collision and both vessels can move freely. If a risk of collision could develop under present courses and speeds, such as a “constant bearing, decreasing range” situation, the Rules will require an early and substantial action by change of course and/or speed.

“Maneuver out of misunderstanding”

Stage 2: A risk of collision arises when any maneuver affects another vessel. The Rules state that if there is any doubt, a risk is deemed to exist. Approaches are classified as Overtaking, Crossing, or Head-on, and specific Rules apply based on these situations. Each vessel can then be designated as Stand-on or Give-way based on their relative approach position and course. The Give-way vessel must slow, stop, yield, or pass behind the Stand-on vessel, who shall maintain course and speed to provide predictability for the Give-way vessel. Let’s not forget Rule 18 which prioritizes certain vessels’ restrictive maneuvering capabilities under a hierarchy or pecking order, for example, powerboats yield to sailboats.

First, identify which one of the three types of encountering situations apply, determined by the relative bearings, courses and speeds between the vessels.

- Rule 13 – Overtaking

- Rule 14 – Head-On

- Rule 15 – Crossing

Once the type of encounter (and vessel type within the “pecking order/hierarchy”) is identified, the Rules directing the actions of each vessel can then be determined.

- Rule 16 – Action by Give-way Vessel (Slow, stop, yield, pass astern; avoid, pass safely)

- Rule 17 – Action by Stand-on Vessel (Maintain course and speed; be predictable)

- Rule 18 – Responsibilities Between Vessels (pecking order i.e., Not under command, restricted in her ability to maneuver, power vessel, sailing vessel, etc.)

Initially, with the existing time and distance between vessels, a readily apparent change of course is preferred. (R8(c)) “If there is sufficient sea room, alteration of course alone may be the most effective action.” This is because any change of speed alone may be difficult, if not impossible to see, while a “readily apparent” change of course is, well, readily apparent.

The risk escalates during the approach advance and options become more limited due to the speed, traffic congestion, environmental conditions, natural hazards, and the vessel’s maneuvering capabilities and limitations, including draft, stopping and turning radius. The Funnel concept emphasizes the need for taking early and substantial action, avoiding small speed and course changes which may not be “readily apparent” to the other. Maneuvers must be early and big enough, so they are fully understood.

Operators must remember that while avoiding collision with vessel A, they must also beware of the effect of the maneuver on vessel B or C. Rule 8(c) directs the action “… to avoid a close-quarters situation provided that it is made in good time, is substantial and does not result in another close quarters situation.”

“Half of preventing collisions is you knowing what you’re doing; the other half is to be sure that the other ship knows what you’re doing.”

Stage 3: Now in a close-quarters situation, each vessel must adhere to the Rules that apply to the roles assigned to each vessel as either Stand-on or Give-way as the situation dictates. By following the Rules with early maneuvers, close-quarters, immediate danger and collisions can be easily avoided. There is still time to maneuver within the Rules as the vessels’ gap continues to diminish.

Per Rule 17(a)(ii) the stand-on vessel “may take action by maneuver alone as soon as it becomes apparent…” the Give-way vessel “is not taking appropriate action in compliance with these Rules.” This means rudder action only; no decelerating ~ at least at this point. Courts have held that the Stand-on vessel can be held liable if rudder action is taken too early.

This maneuver happens before the vessels reach the point where they are in immediate danger of collision. Sound signals are used to communicate intentions and responses to each other within Rule 32 Maneuvering and Warning Signals.

Vessels being operated with Good Seamanship, will have the expectation that there may be an unexpected event, such as a natural hazard to navigation, or hull, steering or machinery failure on either vessel, or even that a medical emergency may suddenly afflict an operator. Good defensive driving provides a safety bubble, escape routes and contingencies. In our case, “Be Prepared” means ready to take the proper action if, and when needed.

Stage 4: Continued violations of the Rules by either or both vessels, for any reason, can lead to an Immediate Danger / In extremis situation. Once the vessels reach a position where collision cannot be averted by the Give-way vessel alone, it becomes not only the right, but also the express duty of the Stand-on vessel to take such action as will, in the judgment of her master or commanding officer, best aid to avoid collision, including departure from the Rules.

R17(b) When the Stand-on vessel “finds herself so close that collision cannot be avoided by the action of the give-way vessel alone, she shall take such action as will best aid to avoid collision”.

This departure from the Rules is also addressed under Rule 2(b), Responsibility, which not only authorizes and allows for, but may even require a departure from the Rules whenever necessary to avoid immediate danger posed by a danger of navigation or collision. At this point, whatever it takes to avoid collision becomes acceptable, barring another collision or grounding.

In extremis, meaning “at the point of death” in Latin, describes a situation where a collision can no longer be avoided solely by the actions of the give-way vessel alone; the danger is so immediate that it requires maneuvering by both vessels in their attempt to avoid collision.

Vessels are in extremis whenever the situation advances to the point where, because of the proximity of the vessels, adherence to the normal rules is reasonably certain to cause collision. It is only at this critical point that deviation from the Rules is permitted. Departing from the Rules prematurely may lead to a collision, which could be a violation if not justified. The burden of proof falls on the vessel claiming the departure was necessary. Both necessity and immediate danger must be present. R17(d) “This Rule does not relieve the give-way vessel of her obligation to keep out of the way.”

“Prudence is the assumption that things invariably go wrong; it is the ingrained ability of spatial awareness and the need for sea room, the likelihood that the person on the other bridge does not comprehend the collision rules and is mad, blind, or drunk.”

Two objects attempt to occupy the same space at the same time.

Stage 5: Collision. At this point, no less than 14 Navigation Rules have been in force, yet they have failed to help prevent this collision. The small ends of the Funnels, or Cones, finally overlapped, and the encounter ends with two vessels unsuccessfully attempting to avoid collision, while successfully occupying the same space at the same time. The pre-collision maneuvers, circumstances, and situation details become crucial to determine how and why a predictable and preventable collision became the result.

“Court decisions in an overwhelming number prove that nearly all marine collisions follow violations of the rules of the road. The inference is that the rules, if implicitly obeyed, are practically collision-proof.”

Good Seamanship

In conclusion, vessel collision investigations involve evaluating the actions taken by each vessel before, during, and after the collision occurs. The Funnel helps by breaking down what happened when, which Rules were violated, and any actions taken, which could be judged as Good Seamanship or Poor Seamanship. These actions include “taking precautions required by the ordinary practice of seamen”. Some are common sense, like fuel management, emergency preparedness, situational awareness, and defensive driving. Others relate to skills such as piloting and navigation, familiarity with all systems and equipment on board, local knowledge, vessel handling, and passenger management (vessel trim/seating and behavior).

If there were a comprehensive list for “taking precautions required by the ordinary practice of seamen,” it would be quite extensive and always evolving due to technological advancements, including new types of electronics, power, propulsion systems, hulls, and now self-driving craft.

And what is “Good Seamanship”? It may depend on and consider the training and experience of the operator. Professionals certainly are, and should be held to the highest standard, but others may not be held to the same standards. One browser defined “good” as everything from acceptable, satisfactory and positive to excellent, exceptional, and superb. It’s much easier to define “Poor Seamanship”; “Operator failed to do this, that and the other thing.”

Below are a few highlights relating specifically to actions in the Funnel:

- Considering all dangers of navigation and collision.

- Avoiding tunnel vision and distractions.

- Checking that the direction is safe before making a turn.

- Being aware of how your maneuvers affect other vessels.

- Avoiding short-range passes that limit reaction time for emergencies.

- Preventing the ship from running aground.

- Taking action to minimize damage when collision is inevitable.